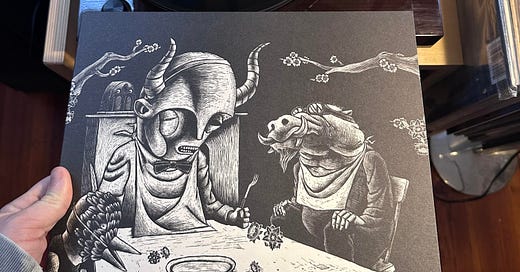

Before He Tore it all Down April 12th: Twenty Years of Okkervil River's 'Black Sheep Boy'

An album chronicling the pain of addiction to drugs and other people

Will Sheff loves music, and so it’s no accident that some of his best songs, albums, and ideas reference other artists; their songs, their lives, and their struggles. Plus Ones references both those added to a guestlist at a show and 99 Luftballons. Triumphant album closer John Allyn Smith Sails combines the suicidal ideation of poet John Berryman with the tune of Pet Sounds hit Sloop John B, exploding into full-on cover territory by the end. And when Sheff writes a eulogy for his own band (!) with Okkervil River RIP he chronicles the painful demise of 80s R&B group Force MD’s and how Judee Sill died in a trailer park alone, strung out on cocaine and codeine. In the same song, he reflects on the death of his grandfather (also a musician) before the song ends with hope, as a teenage band in a skating rink plays a stirring cover that prompts Sheff to ask them to play it again. Death and rebirth abounds.

It’s no surprise, then, that Sheff’s most personal album, and also one of Okkervil River’s best (if not *the* best) begins with a cover that casts a spell and serves to inspire the whole album: Tim Hardin’s Black Sheep Boy, a song written about his heroin addiction and alienation from his family.

Hardin struggled with addiction his entire life. He died of an accidental heroin overdose in 1980, right when he was planning a comeback.

The album Black Sheep Boy, which turned twenty this month, begins with a fairly straightforward cover of the song, and Sheff has said the song inspired the album, with the Black Sheep Boy character in question serving as an unseen entity that weaves in and out of the songs. Sheff has said the quoted lyrics on rougher, harder songs belong to the “Black Sheep Boy,” and the album climaxes with “So Come Back, I am Waiting,” quite possibly the darkest song Sheff has ever written (and he wrote disturbing murder ballad Westfall, mind you).

The song comes to a stirring, dreary, horn and string blaring rise with the following lyrics:

Don't you know you can't leave his control, only call all his wild works your own?

So come back and we'll take them all on.

So come back to your life on the lam.

So come back to your old black sheep man.

He says, “I am waiting on hoof and on hand. I am waiting, all hated and damned.

I am waiting - I snort and I stamp.

I am waiting, you know that I am, calmly waiting to make you my lamb.”

What takes place between these two songs is a tale of two addictions. There’s a self-destructive woman Sheff is involved with who has been through some bad shit. She’s been abused, she drinks and drugs and disappears, and she loves a cold, callous man who has no reciprocal feelings for her. She is addicted to drugs and also to the darkness that fuels it, the monsters inside and outside her that compel her to return to this behavior, return to the Black Sheep Boy’s flock. And then there’s Sheff himself, a “good guy” who is trying to help this woman, wants to love her, wants her to love him, and won’t give up on her until he realizes it’s pointless.

The power of So Come Back, I Am Waiting is that it treats unrequited love for the darkness that it is. It’s an addiction just as potent and powerful as the heroin that undid Hardin. The song could be from the point of view of this fictitious Black Sheep Boy, a stand-in for the darkness that drives addiction. It could also be a stand-in for Sheff, begging his ex to come back despite everything and figure it out, despite the fact that the three previous songs detail exactly why that’s not a good idea.

The second side of Black Sheep Boy kicks off with A Stone, quite possibly the best song about unrequited love ever written.

Sheff details the things his lover likes (hot breath, warm skin, smiles, lovely words) only to then slip into what she loves, descripting the physical characteristics of a stone in such detail you start to wonder if she’s literally in love with a rock. But no, this is a man, maybe even a series of men who do not care for her at all. It’s unrequited love on top of unrequited love, for even Sheff’s lover wants nothing more than to be told “it’s all her own,” which seems impossible. Sheff confesses to take solace in his friends, to take the blame for everything in the relationship while underlining that his love is “picking pebbles out of the drain.” And he admits, he’s too sensitive, emotional and cares too much to be a stone, but he also says that her love is also pointless. “If it could start being alive, you’d stop living alone,” he sings.

The song ends with a beautiful allegory, as Sheff contemplates the dreams of stones “laid side-by-side, piece-by-piece” until they’re a tower for a woman they’re unable to know. And then things get generational. The queen has a daughter who turns down suitors who bring “fresh bouquets everyday” to remember some knave who brought one rose years ago.

To me, this hits at the generational trauma that comes from side one, particularly in Black, where Sheff details a terrible story of paternal sexual abuse and contemplates revenge, fantasizing about violence against this awful rapist. “You should wreck his life the way he wrecked yours,” he screams, but he’s rebuffed by his partner. “You want no part of his life anymore.” But the song ends with Sheff begging to be “let in through that door.” The abuse has made that impossible. The abuse itself could be the reason for “the stone,” or it could be the stone itself. Either way, there’s nothing Sheff can do, and all his teeth gnashing and begging for revenge is pointless. The damage has been done, and his lover would rather forget it and move on. But can she?

In the next song, Get Big, a duet with Amy Anelle, Sheff understands that his partner needs to “take her medicine,” which includes drugs, getting drunk at clubs, having a lost weekend, even leaving the bar on steady legs with someone who isn’t him. It’s all about growing out of her past. If this is what she needs, so be it, Sheff will give her that space, but deep down he knows this isn’t going anywhere. The song begins with the line “once we get to the end of this song then it will begin again.” The song ends with the line “once we get to the end of this song then another will begin.” New song, same song, same repeated patterns and problems. This isn’t going anywhere. Sheff’s lover needs this behavior, and Sheff needs her, but neither of them are getting any closer to being healthier. It’s all just bringing them closer to the Black Sheep Boy, a monster representing addiction and self destruction.

Sure enough, in the next song, A King and Queen, which closes out side one, Sheff admits, “honey you’re murdering me” before foreshadowing lines from “A Stone.”

Be the princess in that stone tower, crying for that handsome butcher's plight

(And, as some princess might, she still calls him a knight)

But the best thing for you would be queen, so be queen

You're all that I need. Though I know that it never can be

A King and Queen ends with references to sunlight grinding the titular pair to dust, which comes back again in side two with The Latest Toughs, where sunlight (the best disinfectant, don’t ya know) exposes what’s really going on to Sheff. Yes, it’s death in one sense, and it buries him, but it’s really the death of an idea, a dream, that this relationship is possible, that it contains something good. It’s notable that The Latest Toughs comes after both A Stone and Song of Our So Called Friend, which is where Sheff first realizes that he has to try and let go of this relationship.

Easier said than done. Because after this song we’re back with to “So Come Back, I Am Waiting.” Giving up the ghost isn’t so easy.

The album begins with the cover, but the first official song is “For Real,” which really is a dark thesis for the whole project, in which Sheff details the pain of losing someone and craves to get over it through any means necessary; violence, self-abuse, threats, and the “blinding lights that curtain cast aside.”

If you're really finally mine I need to know that you're not lying and so I want to see you tried

And I don't want to hear you say "It shouldn't really be this way", because I like this way just fine.

This is the Black Sheep Boy part of Sheff that can’t give up the idea that this woman is meant to be with him. And once those curtains are cast aside, Sheff screams, in a chilling, unnerving way “You can’t hide,” over and over again. And like “So Come Back, I am Waiting,” this is about both of him. He knows where this relationship is headed, the exposed sunlight have made that painfully obvious. But it also serves as a dark threat to his lover. He’s let the Black Sheep Boy in, and the Black Sheep Boy knows how to find her.

I think it’s unfair to call Black Sheep Boy a breakup album because that undersells some of its nuance, and Sheff does not center himself throughout the narrative. Still, it’s obvious how personal this was and is to Sheff and the band, who were on the brink of breaking up while recording it, wondering if they had much to give after two relatively unsuccessful albums prior. Sheff was even driven to homelessness to keep up with the cost of the bands commitments, so the darkness seems warranted. Part of the journey for Sheff might be an addiction to being a musician, as it drove him to the brink of ruin. His commitment to that might be another Black Sheep Boy, and makes his allusions to other dead rock stars even more potent.

What I’ve neglected to reflect on is the sound of the album, and the absolute timelessness of it. This does not sound like an early 2000s record. Instead, it sounds like something that could possibly exist in the same era as Hardin’s original, a drug fueled folk-rock 70s opus, or something that could be released today. The strings and horns mixed with bizzare chimes and keyboard interludes gives it a sense of an album that slipped through the cracks of time. It exists in corners and cracks that you can barely see, and Sheff’s delicate, waivering, voice weaves in and out of all the songs - sometimes steady, sometimes breaking, always volatile int he best ways possible.

It’s hard to say how much of an impact Black Sheep Boy had on me, but I will admit one thing: it helped me get through some dark shit myself, and made me feel less alone about some painful realizations and feelings. It’s one of many reasons why Sheff remains one of my absolute favorite musicians. It’s hard to believe it’s been twenty years since I heard this, and yet, that’s part of the albums charm. As difficult and painful and dark as it is, returning to it feels like a bit of a hug, as if Sheff is saying “I know, it’s okay, I’ve got you.”

The album concludes with the unnerving “A Glow,” which sounds like a chilling, eerie ballad that could be played in that Twin Peaks bar. The narrator is accepting someone in despite the darkness they’ve done. I choose to think this is about me and countless others returning to the album over and over again. We all have a glow when we listen to Black Street Boy, and it’s there waiting in the darkness to understand our pain and offer comforting solutions. Either way, as Sheff sings, “there’s no escaping the thing that’s making its home on your radio.”